If you’ve ever scrolled through social media and sighed at the familiar sunrise over a famous western rim canyon or the same view at a renowned viewpoint, it might be time to look deeper. For anyone serious about “landscape photography American West”, the real magic often lies beyond the crowded overlooks. It lies in the quiet side roads, the remote mesas, the little‑visited state parks and back‑country trails. When you photograph these hidden landscapes, you capture not just scenes but discovery, solitude, and story.

We have compiled a complete guide on how to plan, shoot, and produce compelling imagery in the lesser‑known corners of the western U.S. You’ll learn how to identify truly hidden locations, how to handle light, composition and gear in wild terrain, and how to turn your trip into meaningful photographic outcomes. Let’s dive in.

Why the Hidden West Matters for Photography

The American West is saturated with iconic imagery: the Grand Canyon, Yosemite, and Monument Valley. These places are iconic for good reason. But the consequence is that they’re often predictable, crowded, and shot from the same angles. For a landscape photographer eager to leave a mark, turning to the lesser‑visited areas opens up a bigger canvas.

Resources suggest that “the landscapes of the American West are still chock‑full of amazing vistas outside of national park boundaries.” These hidden landscapes offer a rare opportunity to photograph at your own pace, with better vantage points and less competition for light. They also bring out more authenticity and storytelling: you’re not just replicating someone else’s postcard but your own. That’s the edge when your goal is landscape photography American West.

How to Find the Hidden Gems

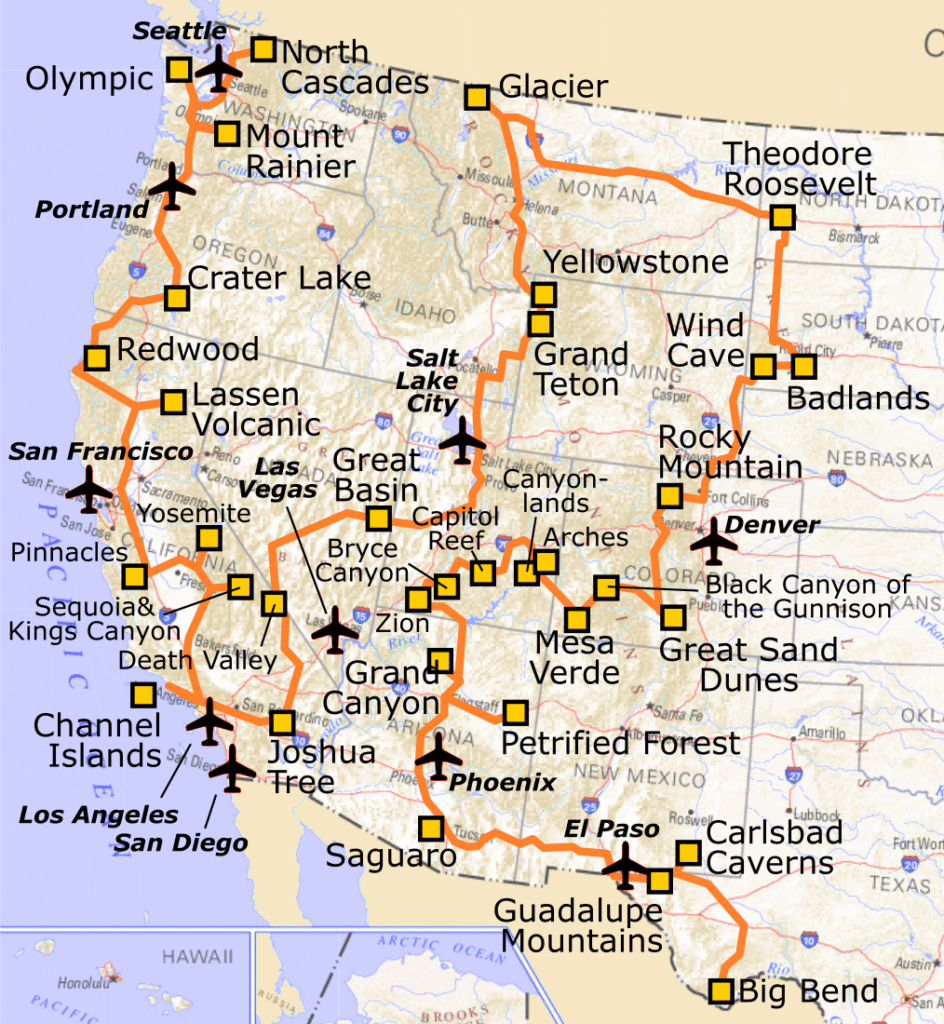

1. Study maps beyond marked trails. Don’t only rely on popular national park map views; look at state parks, Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lands, and areas labelled “wilderness” or “recreation” rather than “tourist attraction.”

2. Read blogs, local forums, and community photography groups. The blog lists lesser‑known photography spots like Devil’s Tower (WY) or Gros Ventre River (WY) near well‑known parks.

3. Go early or later in the day. Hidden doesn’t necessarily mean inaccessible, but timing matters. Arrive before sunrise or stay past sunset to claim the light when most others have left.

4. Accept rougher roads or longer hikes. Some of the best hidden views are off the paved loop. Be prepared for gravel roads, 4×4 tracks or multi‑mile approaches to vantage points.

5. Permit and seasonal research. Some areas might require permits or have seasonal closures. Always check ahead to avoid surprise roadblocks.

By following these steps, you’ll shift your focus from “how iconic is this view?” to “what new angle haven’t I seen yet?”, which is the mindset of effective landscape photography American West.

Gear & Technical Setup for the West

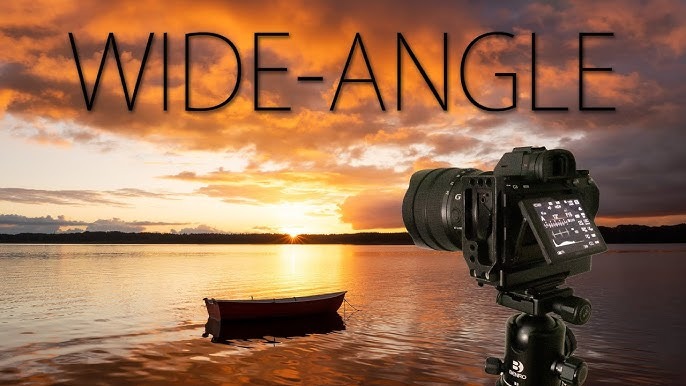

Camera & Lenses: A wide‑angle lens (14‑24mm or similar) helps capture sweeping terrain. A telephoto (70‑200mm) can isolate layers and details, especially in desert or canyon settings.

Tripod & Remote Shutter: In low‑light conditions at dawn/dusk, using a sturdy tripod and remote release makes a significant difference in sharpness.

Filters: A polarising filter can reduce glare on surfaces like water or sandstone; neutral‑density (ND) gradients help balance sky/land exposures.

Backup Power & Storage: Remote locations mean fewer opportunities to recharge. Carry extra batteries, a portable charger, and sufficient storage cards.

Vehicle‑kit: For back‑road or off‑grid work, consider a vehicle mount for your camera gear, a roof‑rack box for tripods, and protective covers against dust/sand.

Plan your technical kit with the assumption that conditions will test you with wind, dust, heat, and fluctuating light. The better your preparation, the more you can concentrate on creativity rather than survival.

Understanding Light, Composition & Landscape Character

Light is everything. The article on desert photography emphasises: “Prioritise great light, the light at these times of day often takes on interesting colours, as light passes through more atmosphere.”Avoid full midday sun for dramatic landscapes—early morning and late afternoon are your golden windows.

Foreground, middle ground, background. Avoid empty frames. Even broad desert scenes need a strong focal point: a rock formation, a lone tree, or lines in the terrain. As one guide says: “Wide‑open spaces … are among the hardest landscapes of all to photograph well … you want to lead the viewer through the image.”

Select your angle. Sometimes you need to move closer or change the lens width to bring purpose. Rather than capturing everything, capture a story: the way light slices through a canyon, the way a road curves towards distant peaks, or the way shadows shift across desert sand.

Use scale and texture. Including human elements, vehicles, or small structures can emphasise the immensity of the landscape. This is especially potent in the American West with its vastness.

Road‑Trip Field Workflow: From Arrival to Capture

- Arrive early to your location so you can explore and scout before golden hour.

- Walk around: Don’t shoot first view you see. Explore different angles, elevations, and vantage points.

- Set up before golden hour: Get your tripod ready, test exposures and filters while light changes.

- Shoot multiple exposures: For high dynamic range scenes (bright sky + dark canyon), bracket shots for later blending.

- Stay after sunset: Post‑sunset light (“blue hour”) can yield soft pastel skies and subtle terrain tones.

- Have a backup plan: If weather or light disappoints, have a secondary location or vantage as a stopgap.

- Keep notes: Jot down gear/settings and location. These field notes become invaluable when you post‑process or revisit locations later.

For the serious practitioner of landscape photography American West, this workflow becomes routine. The effort invested in scouting, timing and setup is what separates the “nice shot” from the “memorable shot”.

Post‑Processing & Storytelling

In processing your images, keep these principles in mind:

- Moderate editing: Enhance what was real. Avoid over‑processing such that the scene becomes unrecognisable. Articles on staging landscapes confirm that the best results still respect what the viewer might have experienced.

- Colour & tone: In desert and canyon terrain, warm light and rich shadows define the mood. Adjust white balance and saturation carefully to keep things natural and evocative.

- Cropping & orientation: Don’t force wide panoramas if a vertical crop brings more impact (for example, a lone tree at the base of a butte).

- Adding story: Embed metadata, location info, and shooting notes so your image isn’t just pretty but meaningful.

- Print & share: A large print brings the sense of scale; sharing images in communities dedicated to landscape photography American West can open critique and new opportunities.

Ethical Considerations & Respecting Place

Hidden landscapes often lie in fragile ecosystems or lands with cultural significance. As photographers, you carry responsibility:

- Stay on trails: Avoid trampling vegetation or disturbing wildlife.

- Respect light and time of day: Don’t camp or shoot where prohibited.

- Be aware of cultural/native land: Some formations are sacred to Indigenous communities. Photograph with permission and respect.

- Leave no trace: Trash, footprints, and drone use stay minimal. When you photograph hidden places, you become part of that story.

- Honour access: Some roads or tracks may be private or require permits-check ahead.

When you treat the land with care, your images will reflect beauty as well as integrity.

Bringing It All Together: Your Hidden‑Landscape Blueprint

To recap:

- Choose less‑visited sites in the American West by mapping beyond the popular parks.

- Plan for quality light, carry strong gear, and hunt angles not yet photographed.

- Accept the back‑road work-long drives, early mornings, dust and terrain.

- Scout, shoot, process with intention. Use compositional techniques, light mastery, and editing that honours the scene.

- Share images that aren’t just pretty, but personal, thoughtful and anchored in place.

When you execute the process above, you’ll align with the deeper aspiration of landscape photography American West-not just to record or replicate, but to interpret and contribute. The hidden landscapes are waiting to be experienced.

Closing Reflections

In the end, your best shot might not come from the most famous viewpoint, but from the turn-off you almost ignored, the early morning hike you almost skipped, or the one stranger‑than‑usual vantage you discovered by staying a little longer. Hidden landscapes of the American West hold that sense of alchemy, where light, place and perseverance meet.

Pack your tripod, turn down the predictable spots, and let the west open up quietly, powerfully, and personally. The lens you point matters. The place you go matters. And ultimately, landscape photography in the American West becomes not just about location, but about connection.